The world’s population will come to almost 10 billion people by 2050, leading to a 70% hike in the demand for food, according to FAO estimates, and undermining humanity’s ability to feed itself. With limited natural resources, such as fresh water and fertile land, achieving the food production levels required to provide the population with protein will become unsustainable. In that regard, a type of phytoplankton called microalgae, with their high nutritional potential and reduced environmental footprint, are emerging as promising candidates in the race to overcome this challenge.

The Institute of Agrifood Research and Technology (IRTA) is currently co-ordinating and leading the ambitious EU-funded ProFuture project, which seeks to develop more sustainable and more competitive microalgae production technologies. That way, nutritional foods that are rich in protein could be obtained using fewer chemical nutrients and less energy.

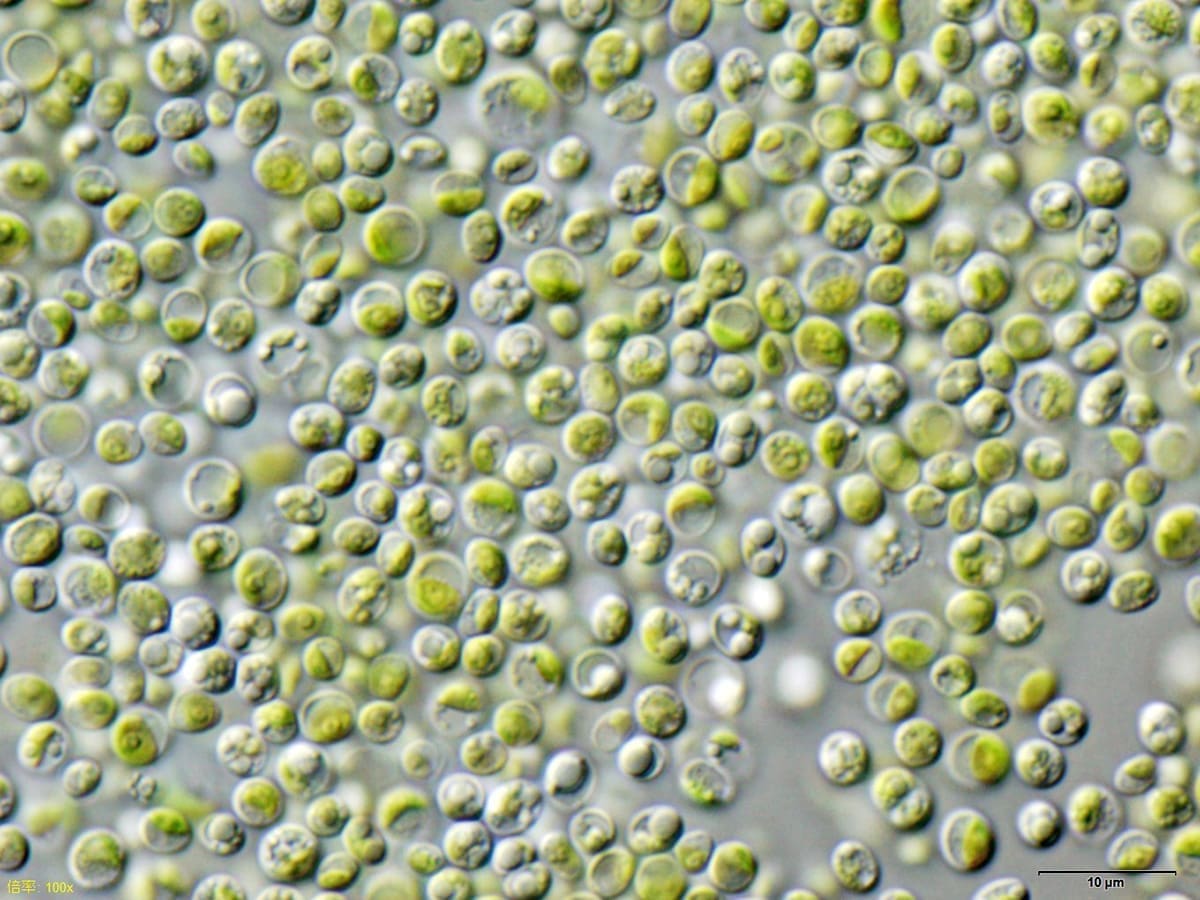

Microalgae are single-cell organisms that can be cultivated in large open pools or bioreactors, and which mainly require sunlight, high temperatures and inorganic nutrients to grow. Their cultivation also requires less land and fresh water than other plant-based proteins. Microalgae have a very high production capacity and provide a biomass rich in protein and fats that, once transformed into a powder, can be used to produce foods such as pasta, bread, animal feed, soup and energy bars.

“Despite having been studied in Europe for many years and especially in the context of biofuel production, the current problem with microalgae is that production remains limited and is not fully industrialised, which means the product’s price remains high,” says IRTA researcher and ProFuture co-ordinator Massimo Castellari.

Overcoming that pitfall is the main objective of the project, which involves 31 European partners, including research centres, businesses and associations. To do so, the team has selected four highly productive microalgae species – two fresh-water species (Lemon/lightly Chlorella vulgaris and Arthrospira platensis, a.k.a. spirulina) and two marine species (Tetraselmis chui and Nannochloropsis oceanica) – which it will use to develop and apply innovative cultivation technologies and techniques to increase production and reduce costs. The initial phase will be implemented in pilot plants in Portugal, in partnership with universities and research centres. The initiative will then be scaled up through the work of nine small, medium and large food and feed companies in seven European countries.

Once the microalgae have been harvested, they are dried and a powder is produced, which becomes the main ingredient for market use. One of the disadvantages of this ingredient until now, when added to food production processes, is that it has a very distinct taste and adds a green colouring to products. Pasta or bread enriched with spirulina are one example of that.

“Our aim with the project is to develop a more purified ingredient that would improve the texture, appearance, taste and aroma of products containing microalgae and thus extend the range of applications,” explains Castellari. ProFuture is seeking to create seven different types of foods: pasta, bread, broths and creamy vegetable soups, energy drinks and bars for athletes, vegan sausages and animal feed.

Making products using microalgae would provide a high quality source of protein for different countries, with the crop-growing system adapted to each setting. “The techniques can even be implemented in the desert, in marginal areas, which means they do not compete with other crops for land. And that is an option could be of considerable interest in countries such as Spain, where desertification is on the rise,” says the researcher.

ProFuture is a four-year project that has received €7.78 million in funding from the EU Horizon 2020 programme for research and innovation.