All over the planet, tiny synthetic invaders are infiltrating aquatic, terrestrial and even aerial habitats. Measuring less than five millimetres, microplastics are so small they are almost invisible to the human eye, but their omnipresence is having increasingly noticeable effects on ecosystems and threatening their biodiversity. Bodies of fresh and salt water are among the environments in which such particles are most widespread. Eight million tonnes of plastic end up in the sea each year, and images of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, the huge plastic island in the Pacific Ocean, have led to numerous campaigns and studies. Most of them have focused on macroplastics, however; society in general and environmental sciences alike have largely overlooked microplastics until recently. “Many natural areas we believe to be in pristine condition are polluted too, whether we see it or not,” explains Maite Martínez-Eixarch, a researcher from IRTA’s Marine and Inland Waters programme.

That situation poses a number of challenges, one of which is to improve microplastic identification and monitoring techniques, with a view to understanding where microplastics come from, learning how they behave and, ultimately, taking steps to reduce their impact. With that in mind, a team from IRTA, coordinated by Martínez-Eixarch, launched the BIO-DISPLAS project in 2021, with support from the Biodiversity Foundation of Spain’s Ministry for the Ecological Transition, to determine the extent of the distribution of microplastics in the Ebro Delta’s aquatic environments and develop a system to classify them automatically. According to a 2019 study by the Institute of Environmental Science and Technology (ICTA-UAB), the Ebro funnels 2.2 billion microplastics into the Mediterranean Sea every year.

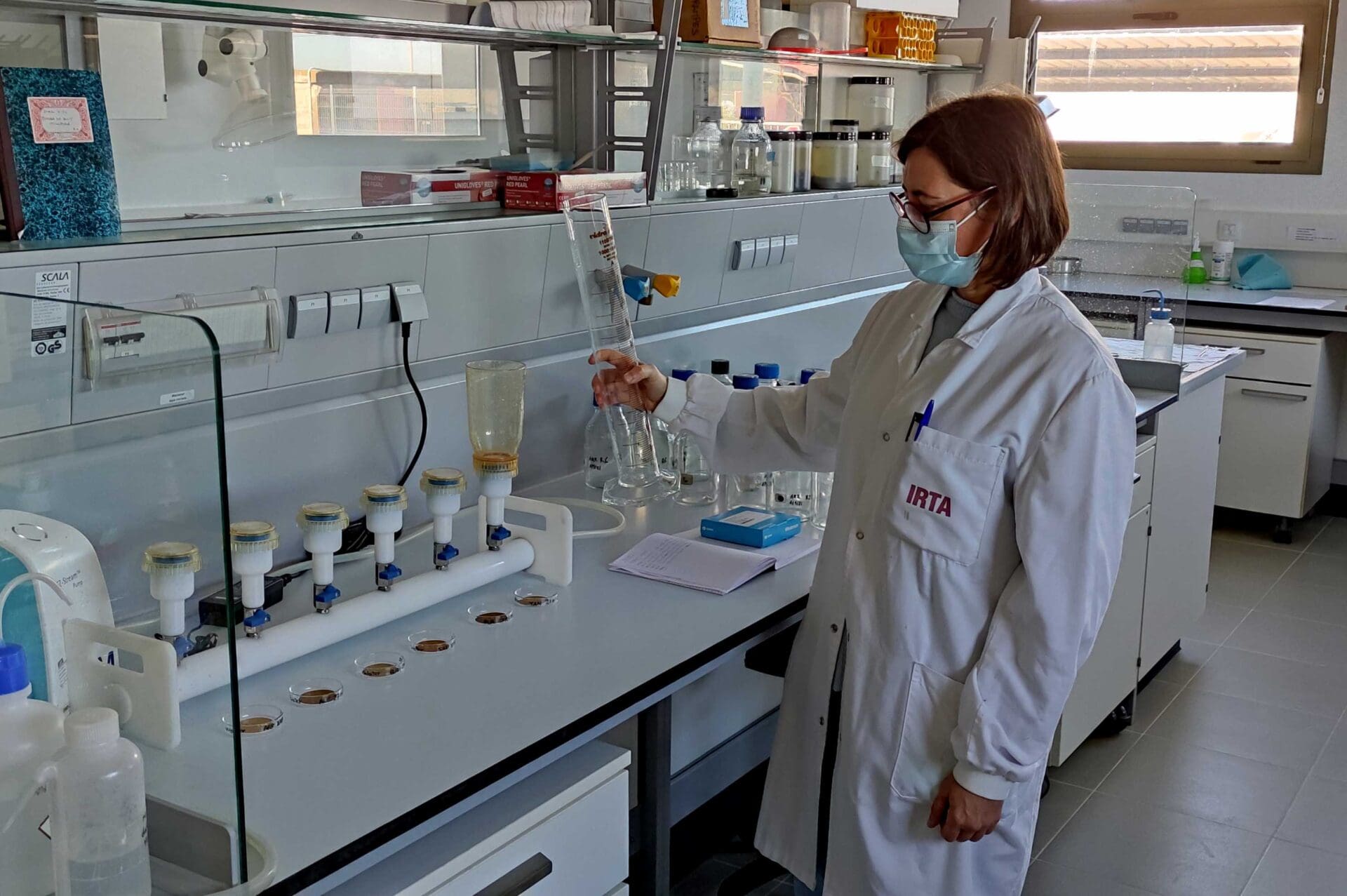

The ICTA-UAB study revolved around ramples tanek from sandy beaches, surface waters and the bed of the estuary, whereas the BIO-DISPLAS project is based on water and sediment samples from five of the Ebro Delta's lagoons and one of its ricefields. “We are currently refining the method for extracting microplastics in the laboratory to adapt it to the types of samples we are using and ensure correct extraction,” remarks Rosa Trobajo, a researcher working on the project. Once the microplastics have been separated from natural residue, the particles will be counted and classified according to their size, colour and structure type (e.g. fibres, fragments or films). The result will be a table showing the polymer concentration in the ecosystem’s different habitats.

IRTA will also use the data in question to develop a computer model to identify, count and measure microplastics in images obtained with microscopes or stereomicroscopes. Following some initial manual input, the application will gradually fine-tune itself during the process, thanks to a machine learning algorithm, and will eventually be able to detect and classify microplastics on its own. The visual technology involved is already used in other areas, such as microbial colony counting. “It will save us time and effort and let us standardize and automate future counting processes,” says Carles Alcaraz, the IRTA researcher responsible for programming the model.

All the team’s work will provide a first accurate picture of just how widespread microplastics are in the Ebro Delta, laying the groundwork for future monitoring and research activities. “We will be able to see, for instance, how microplastics affect the dynamics of the ecosystem’s natural flows or how their distribution is related to environmental factors,” states Martínez-Eixarch. A complete picture of the situation will also make it possible to work out where the microplastics in the delta come from. Based on their origin, microplastics can be divided into primary microplastics (which are already microscopic when manufactured) and secondary microplastics (which originate from the fragmentation of larger plastic items).

Studies such as that conducted by the environmental organization Associació Hombre y Territorio in 2020 have shown that microplastics are ubiquitous in most of the Spanish mainland’s hydrographic network. Nonetheless, “there is still a great deal to clarify in terms of distribution and of how such polymers affect different habitats,” as Martínez-Eixarch points out. Synthetically produced materials can alter dynamics such as the nutrient cycle and the decomposition of organic matter. Furthermore, as has been observed in Catalonia in the case of seabirds, microplastics enter the food web, which includes humans, and can be toxic or disrupt our hormone systems.

The BIO-DISPLAS project, which is being carried out by staff working on IRTA’s Marine and Inland Waters programme in Sant Carles de la Ràpita, will run until 2023 and is being supported by the Biodiversity Foundation of Spain’s Ministry for the Ecological Transition. The project also involves the Spanish NGO SEO/BirdLife, which is providing volunteers for laboratory work and will be participating in activities for the transfer and dissemination of results.